Reena Blanco, MD

rnarwan@emory.edu

Alesia Fleming, MD, MPH

aflemi2@emory.edu

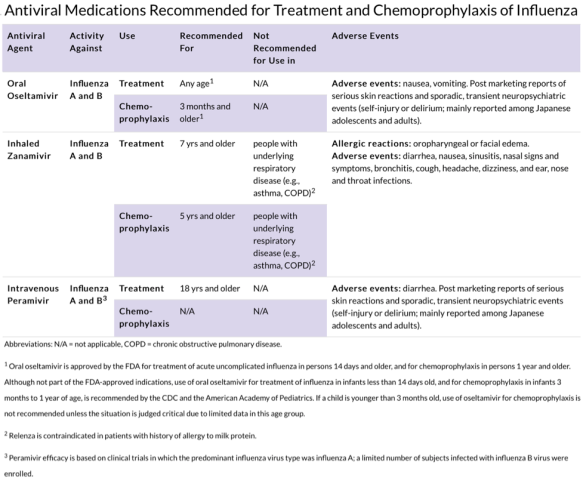

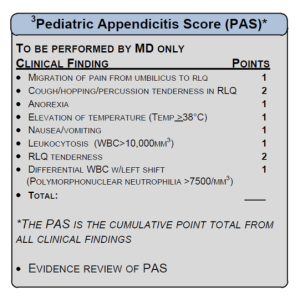

Acute appendicitis is the most common, non-traumatic surgical emergency encountered in children. Early identification can lead to timely removal preventing perforation and its complications. Abdominal pain is a common symptom in the emergency department. To help differentiate the surgical from medical emergencies, CHOA emergency medicine, surgery and radiology teams collaborated to develop the suspected appendicitis clinical guideline.

The broad goals of the team were to:

- Identify children with the highest risk of appendicitis

- decrease utilization of abdominal CT to diagnose appendicitis

- Increase utilization of the Pediatric Appendicitis Score (PAS).

- Streamline and standardize clinical evaluation

- Decrease time to diagnosis and definitive care

The guideline was implemented in 2013 using the PAS as a common language tool to better communicate across services. Patients 5 years and older with abdominal pain for less than 72 hours** suspected of having appendicitis are evaluated according to the pathway with screening labs, given an initial IV fluid bolus and pain medication. After this, the PAS score is calculated and used to further guide care and communicate across services for next steps.

Patients with a PAS of 0-4 have a low suspicion for appendicitis. The physician should consider other diagnoses. There is always a risk that the patient may develop further symptoms as disease progresses therefore if discharged home, these patients need to be seen by their PCP within 24 hours for re-evaluation.

A PAS of 5-7 is equivocal for appendicitis and diagnostic imaging or surgical consult is warranted. The guideline promotes US as the exam of choice for initial evaluation. Ultrasound has a sensitivity is 98% and specificity is 92% in identifying appendicitis in those where the appendix was clearly seen. In addition to eliminating exposure to ionizing radiation ultrasound can evaluate female patients for ovarian torsion which is part of the differential of appendicitis. The exact correlations between radiation exposure and cancer in children is not known, and utilizing alternative imaging modalities such as ultrasound limit exposure to ionizing radiation.

If the patient has a PAS >8 there is a high suspicion for appendicitis, imaging is not required, and surgery should be immediately consulted.

The guideline does not represent a professional care standard and physicians will need to be prudent in determining most appropriate care, but it does offer an approach to abdominal pain that should help with efficiency of care and ultimate outcome of our patients.

**exclusions outlined in clinical practice guidelines on md.choa.org under

clinical excellence->clinical practice guidelines